LISTEN: Freedom of Expression at Cornell – Academic freedom

This is the last of my three stories about freedom of expression at Cornell University this year. Here are links to the first and second stories.

The academic theme at Cornell this year is “Freedom of Expression.”

In earlier stories, we reported about the general mood at Cornell around free speech, and students' opinions about their free speech rights. Today, you’ll hear from some faculty about academic freedom, what it means, and whether it, too, is being challenged.

WRFI requested an interview with a Cornell administrator about free speech on campus. Our request was denied. Celia Clarke reports.

Academic freedom isn’t exactly the same as free speech. Risa Lieberwitz is a professor in Cornell’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations. She’s also head of the Executive Committee of the campus chapter of the American Association of University Professors. It represents professors but also graduate student instructors and other university staff, like library workers. And a leader in the Faculty Senate.

"Academic freedom for faculty to exercise in their teaching, in their research, in their governance, in their speech outside of the classroom on or off campus, whether it's in their disciplinary area or not. All of that comprises academic freedom," she said.

Lieberwitz said many faculty members are concerned about changes happening on campus in a year meant to celebrate freedom of expression.

"What many of us have been pointing out is the contradiction between that being the theme year, and now the focus on restrictions on freedom of expression, which, which, to me gives the message that the university administration is itself acting out of fear," she said.

She continued, saying a major source of that “fear” is from outside the University. "It’s acting out of fear from the Congress, you know, asking for documents through the congressional committee that's really inappropriately, inappropriately interfering with universities,".

Representative Jason Smith the Republican chair of the House Ways and Means Committee had recently sent a letter to seven schools including Cornell saying they weren’t doing enough about antisemitism on campus. He connected their actions to their schools’ tax-exempt status. That’s not the only thing Leiberwitz sees driving the “fear” she senses from the administration.

"It's acting out of fear because of a Title VI investigation that's taking place," Lieberwitz said.

Last November, the U.S. Department of Education started investigations into Cornell and six other schools for alleged violations of Title VI. It prohibits schools getting any federal funding “from discriminating based on race, color or national origin.” The allegations specifically relate to “antisemitism, anti-Muslim, anti-Arab, and other forms of discrimination and harassment.” Neither the Department of Education nor Cornell officials will say whether the incidents are antisemitic, anti-Muslim or both.

Lieberwitz said there might be another source of concern for administrators closer to home.

"And it's acting out of fear, perhaps from donors, who may be pressuring the university in ways that aren't coming to light, but they may simply be there. So I think that and it might be fear from parents," she said.

Lieberwitz says how the administration seems to be reacting to these pressures is troubling to many faculty members.

"This is no way to run a university. A university should be brave. We should be pushing in our teaching in our research in our governance bodies, in our speech, on campus and off campus. We should be pushing against the status quo, questioning the status quo, seeking new avenues, seeking to confirm what we think we know, or question what we think we know in different ways. And so to act from fear is to undermine the basic principles of the public mission of the university," she said.

Paul Sawyer is a professor emeritus of the English Department. He says that bravery described by Lieberwitz includes what faculty do in the classroom.

"It's very important for universities to be independent examiners of truth, okay, to bring up issues such as, say, the oppression of Palestinians of Israel, that might be taboo when it comes to, let's say, watching MSNBC, or listening to a press conference in Washington. It's very important that universities not simply follow what political dogmas, whatever political documents are being circulated by Washington in the mainstream press," said Sawyer.

As mentioned in an earlier story, protest is nothing new to Cornell.

The Coalition for Mutual Liberation (the CML) is a collective of about 40 student organizations at Cornell. It was formed earlier this academic year. They have organized several rallies in support of Palestinian rights in Gaza, calling for a ceasefire, and demanding the university to divest from companies with ties to the Israeli military. They started protesting before the Interim Expressive Activity policy was introduced. Some of them think the policy deliberately targets their activism. University officials stated the work on the policy began last Spring. CML protests continue partly in defiance of the interim policy and about 10 students have faced disciplinary hearings so far.

"That's unprecedented that didn't happen in the divestment movement," he said.

Sawyer’s referring to the nationwide anti-apartheid protests in the 1980s when students and faculty demanded Cornell divest from companies with ties to apartheid South Africa.

The Interim Expressive Activity policy has changed the campus this year. It’s widely criticized by staff, faculty, and students. Some faculty and staff say it's affecting academic freedom, too. Some, especially untenured faculty say it makes them second-guess what and how they teach in class.

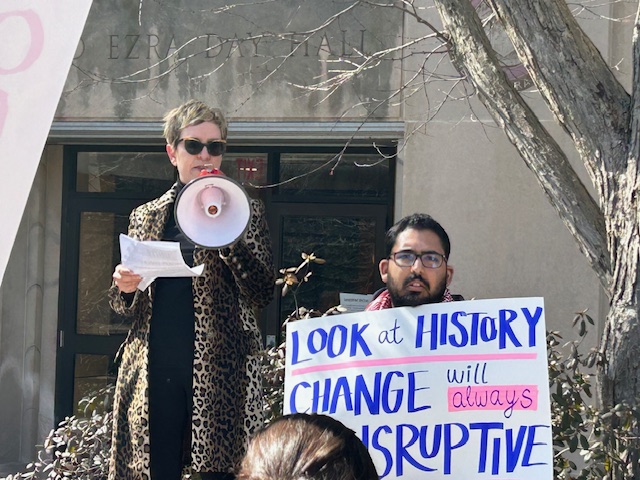

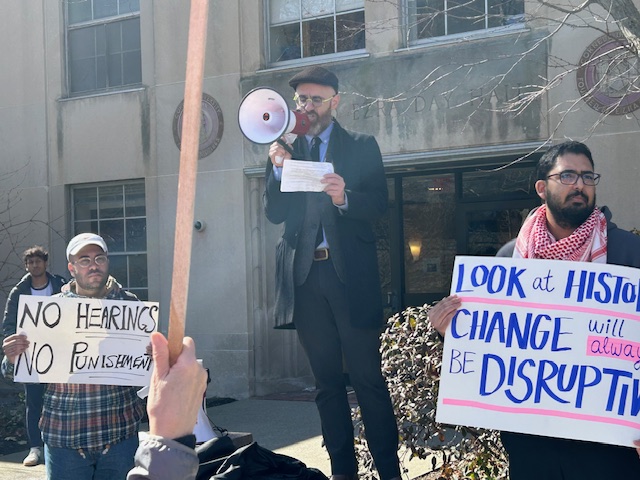

On March 12 about 100 faculty and staff rallied in front of Day Hall, the administrative building. They were protesting the interim policy and support their students who’ve been protesting for months.

Some carry signs on sticks that say, “This poster is larger than 8 x11” and “Let our students scream.” They refer to the interim policy restrictions on the size of signs and what they’re made of. It also prohibits signs carried on sticks.

Tracy McNulty was one of the speakers. She’s a professor of Comparative Literature. She took the megaphone, stepped up on a low wall and spoke to the gathered crowd.

"Sometimes, I think we're confused about what this concept is really about. Academic freedom is not just the promise of protection from the consequences that might follow from our actions but the responsibility that comes with being a student and a scholar," Mcnulty paused briefly as the crowd cheered lowdly for the first of several times as she spoke.

Ten days later McNulty co-authored a letter published in the Cornell Daily Sun. She and other signers defend the CML’s (Coalition for Mutual Liberation) rights to protest without facing punishment for speaking out against the university.

A flurry of letters was published in the Cornell Daily Sun in March before and after the faculty protest. Here’s a rundown of some of the key ones.

March 11 - Anthropology faculty members published a letter opposing the interim policy.

March 12 Faculty, staff, and students protest in front of Day Hall. The Anthropology letter is read.

March 21 - Pollack received another letter from Congress. This one singled out the CML protests’ and asked Pollack to provide proof that the student leaders were being punished for their “disruptive” protests. The letter again suggested that Cornell’s tax-exempt status might be in jeopardy.

March 22 - A letter by McNulty and other faculty supporting student protests and the CML is published.

March 26 -Pollack and Provost Michael Kotlikoff published their first public statement about the protests and the general mood on campus around the interim policy. The letter criticized the faculty and CML as “going too far” and disrupting university activities. They wrote, that there should be “a robust campus discussion about what ‘disruptive’ means: how much is tolerated in support of free expression and where the line is drawn.”

And this isn’t all -- there’ve been other letters opposing the interim policy and the administration’s reaction to student protesters. There’s been one published that criticized CML, saying they “glorify terrorism” and that their protests are “a concerted effort to silence other students through mob intimidation.”

Back in front of Day Hall on March 12 Government professor Alexander Livingston takes the megaphone. He’d later add his name to the letter defending student protesters.

"Disruption is no threat to speech. Disruption is often an invaluable form of democratic speech. Disruption becomes speech when voices are ignored. Disruption becomes speech when demands for civility and deliberation serve to discredit dissent, inequalities of influence and power. Disruption become speech when agendas are set by keeping inconvenient issues off the table, stifling debate, and policing expression. This is disruption as a demand for real dialogue, ambitions, and rhetoric of free expression denies," Livingston's comments were greeted by loud cheers of support by the crowd.

More faculty letters to the editor have been published in the Cornell Daily Sun opposing the interim policy and supporting student activists' rights to protest. They have come from the Anthropology Department core faculty before the March 12 protest, and afterward the Near East Studies faculty, individual faculty members, and Cornell library workers.

The administration has made some changes to the Interim Policy to address some of the criticism of the interim policy. The administration has also stated that the policy is still being developed.

Later on March 12, Tracy McNulty (the Comparative Litarature professor) had more to say about the responsibility of academic freedom.

"I want to speak now to my colleagues among the tenure-line faculty, right now. There are very few people on Earth who have the same job security as a tenured faculty member in the United States. So when we have tenure and say nothing, we're not just failing to use our platform to call out lies and doublespeak and hypocrisy. We’re also deeply complicit in sustaining the fiction that we ourselves stand for academic freedom. Not only does it [protect us with a] “Get Out of Jail Free” card, but as a sacred trust kind of profound responsibility. Because implicit in the very idea of academic freedom is the promise and the expectation that we as faculty will not be silent," she told the assemble group.

NOTE: Throughout my reporting for these stories, I was unable to speak to people who support the interim policy or who object to the ongoing protests.